BY SHRIKANT RANGNEKAR

For successful transmission into the broader culture, great artwork must be copied into different mediums, by different artists with different visions and different capabilities. In the new Atlas Shrugged movie, this process is well at work.

I watched the preview screening of Atlas Shrugged Part 1 in New York City last week, and here is my take on it.

This is a sincere attempt to portray Atlas Shrugged. The production team genuinely liked and respected Atlas Shrugged and it appears they tried to portray it to the best of their ability within the constraints they had.

Making a movie is a large-scale endeavor, and working for nearly two decades to bring the movie to fruition required considerable tenacity, resourcefulness, and purposefulness. I must thank especially John Aglialoro, the producer who spearheaded the project, for making that happen.

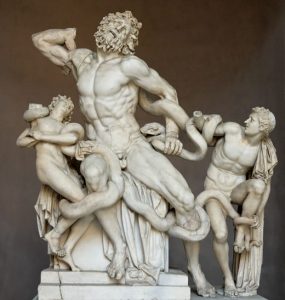

My overall impression of the movie can best be described by an analogy. A few years ago, I began studying the cuture of Ancient Greece. I did so by immersion into Greek literature, visual arts, history, philosophy, science, descriptions of daily life and customs, learning rudiments of Ancient Greek language, and visiting Greece.

I found the Ancient Greek culture to be so dramatically and radically different from the culture around us that most modern attempts to portray the culture captured only the outward trappings while missing the core view of man that animates the culture.

Similarly, this movie does a good job of capturing the political, economic, and social aspects of Atlas Shrugged while missing the deeper moral, psychological, epistemological, and metaphysical aspects of the novel.

Capturing the political, economic, and social aspects of Atlas Shrugged is an achievement itself.

As someone who deeply loves Atlas Shrugged, and knows that the heart of Ayn Rand’s achievement is metaphysical, epistemological, psychological, and moral, I was left with a sense of emptiness — of seeing a work of art that looks like Atlas Shrugged on the surface, but with something critical missing.

Capturing the political, economic, and social aspects of the novel is an achievement itself, and I certainly enjoyed seeing that brought to life on the screen. That said, the movie versions of Ayn Rand’s characters were oddly similar to people I see in New York every day. They talked, looked, moved, and related to each other somewhat like most people do today, not in the highly stylized manner of the novel’s characters. I had the odd sensation that I was watching a world halfway between Ayn Rand’s world and my New York today — a hybrid of naturalism and romanticism.

The production quality is high and the movie is well-executed visually.

The clearest and most damaging way in which this was executed was by unnecessary replacement of Ayn Rand’s dialog by those of the movie’s writers. My guess is that having the characters talk more like most people today was an attempt to make the characters more “believable.”

Though I know next to nothing about movie making, I have one sure-fire piece of advice that could make Atlas Shrugged Part 2 significantly better while reducing production costs: Please, please use more of Ayn Rand’s lines.

The good portrayal of Hank Rearden and a dramatic and innovative use of “Who is John Galt?” lines were the highlights of the movie for me. The production quality is high and the movie is well-executed visually. I again thank the production team for making this movie and I encourage my friends to see it. It is not an experience you want to miss.

Let me expand on the analogy to modern portrayals of Ancient Greek culture. The central difficulty in modern portrayals of Ancient Greece lies in what I will call the “cultural distance” between the modern view of man and the Ancient Greek view of man.

The cultural distance between Ayn Rand’s view of man and the modern view of man is equally large. Some of us who have spent years internalizing and making operational in ourselves Ayn Rand’s metaphysical, epistemological, psychological, and moral principles, are aware of this distance, through the sheer effort it has cost us to traverse it.

Making a great movie based on a great book is not the mere translation, but the creation, of an entirely new artistic integration.

The cultural distance between Ayn Rand’s view of man and the modern view of man is equally large. Some of us who have spent years internalizing and making operational in ourselves Ayn Rand’s metaphysical, epistemological, psychological, and moral principles, are aware of this distance, through the sheer effort it has cost us to traverse it.

Traversing that cultural distance in one’s own person, however, is easier than making a piece of art that objectively enables others see the new vision of man in a concretized form across that massive cultural chasm. That is precisely Ayn Rand’s achievement in creating Atlas Shrugged. Even with her phenomenal artistic skill, it took her over 1000 pages and over a decade of unremitting labor to make her vision real.

Because a movie is a distinct art medium with its own unique constraints, strengths, and weaknesses, making a great movie based on a great book is not the mere translation, but the creation, of an entirely new artistic integration that matches the original in meaning. It would take an artistic achievement on the order of Ayn Rand’s to make a movie that fully lives up to the novel. All this needs to be kept in mind while judging the movie.

Romans revered Greek sculpture and made a massive number of copies of it, but they never could capture the deeper meaning — the dynamic, living soul of the Greek sculpture.

We need both the Greek ideal and the Roman transmission network.

In focusing on the political, economic, and social aspects of the novel as opposed to its deeper spiritual aspects; in using a more colloquial dialog and characterizations to replace Ayn Rand’s highly stylized one; and by using the extremely efficient mechanism of the movie medium itself — the Atlas Shrugged movie does to the novel what Romans did to Greek art. The movie is a Roman copy of a Greek original.

While the Greek sculpture is far superior in esthetic value, Roman sculpture through its sheer quantity and superlative transmission ability has served a critical cultural value as the transmission mechanism for the Greek ideal. Just as the Renaissance sculptors discovered Greek art largely through their Roman copies, this movie trilogy will help a wider audience discover Atlas Shrugged.

Both Greece and Rome are the foundations of our civilization. We need both the Greek ideal and the Roman transmission network. While it would be wrong to blame the Roman transmission network for not having the Greek delicacy, it would also be wrong to let ourselves forget the full grandeur of the Greek ideal, due to the ubiquity of Roman copies.

With this in mind, I raise a toast to both — to Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged and to Atlas Shrugged the movie — each for what they are.

Shrikant Rangnekar lives in New York City. This article originally appeared on his blog, where he is still updating the original post in response to reader feedback.